This article was written by NYG&B Summer Intern Jake Garfinkle.

The early 20th century saw an influx of Jewish immigrants to New York City, with 1.5 million Jews living in the city by 19201. Jewish life flourished in New York City and brought about the rise of landsmanshaftn, which were societies for immigrants from the same place in the Old Country.

My ancestors were actively involved in landsmanshaftn, and some even founded their own landsmanshaft. While these organizations were so important to Jewish community, their decline over the century has led to a lack of knowledge about them.

This article explores what landsmanshaftn are and how they clue us in on how our ancestors formed community, navigating life in the new country while maintaining ties to the Old Country.

My ancestors’ landsmanshaftn experience

My Tinter ancestors were from a shtetl, or small predominantly Jewish town in the Old Country. Most of the family left the shtetl, called Stebechve, in the early 20th century, choosing to settle together in New York City. Many other Jewish families from Stebechve also left, and New York City quickly became home to a large diaspora community of Stebechver Jews.

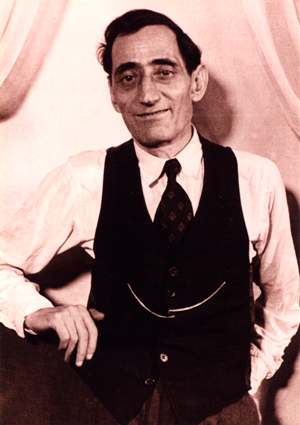

great-great-grandfather of Jake Garfinkle.

Abraham was a founder of the Stebechver

landsmanshaft and served as its secretary.

These Stebechver Jews were in for quite the culture shock. The shtetl was a place of close community and kinship, with maybe 500 Jewish people at the turn of the century, while New York City was a bustling hub, home to millions of people. Seeking to make a big city a little smaller, the heads of families from Stebechve came together in 1918 to form the Chevra Beth David Anshe Stebechve, filing the paperwork to legally incorporate seven years later. According to grandchildren of founders, the primary role of this landsmanshaft was to facilitate communal burial of Stebechve Jews, but research suggests they also prayed together. My great-great-grandfather, Abraham Tinter, was the secretary of the society at one point, and his son, Sidney, followed as president.

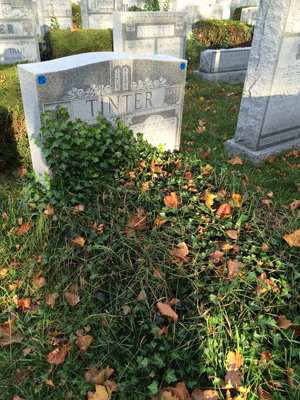

I first learned about the Chevra Beth David Anshe Stebechve when I went to the graves of my Tinter ancestors on the outer edge of Queens. The whole family is buried together among other landsleit, or people from the same place in the Old Country. The landsmanshaft’s plot is demarcated by a set of pillars, inscribed with the names of the Chevra founders. Walking through the pillars, I found myself surrounded by the names of relatives and connected families.

Despite leaving Stebechve, these families chose to stay together in New York, forming a community in life. They also chose to form an enduring community in death, buried together, with their gravestones constituting a new physical space that is in New York but rooted in Stebechve. How incredible is it that a dozen families from rural northwestern Ukraine ended up buried side by side in Queens? This was through the power of the landsmanshaft.

What are landsmanshaftn?

The experiences of my ancestors became clearer after understanding what landsmanshaftn are and what roles they played.

Landsmanshaftn were as varied as the people who formed them. However, landsmanshaftn were generally organizations for people from the same place in the Old Country, who came together for community, prayer, mutual aid, and/or burial2.

Association at Washington Cemetery

in Brooklyn, New York.

Some landsmanshaftn were more involved in social aid and benefit activities, giving small amounts of money to widows and sick members, helping new immigrants adjust to the country, and finding work or a place to live3. Identifying an ancestor’s landsmanshaft membership can help identify additional information about them, like the community they were involved with and where they were from.

Some places in the Old Country—like big cities or regions—had many landsmanshaftn organized around them. Krakow, a city my maternal ancestors came from, had a myriad of landsmanshaftn, though my great-great-grandfather joined the Krakauer Friends Association. The reasons for different organizations could be the timing of when the immigrants came over, quarrels between members of the community, different social goals or focus, and varying ideological bends.

Many landsmanshaftn were also organized around synagogues, which were themselves often organized by Old Country origins4. Synagogues organized by New York City proximity also often had landsmanshaft-like organizations, though not composed of landsleit.

New York City Landsmanshaftn: A history of community

Eastern European Jewish landsmanshaftn existed in New York since the mid-19th century with the founding of The Krakauer Society, incorporated in 18555. Over the course of the 19th century, as more Jewish immigrants came to New York, the number of landsmanshaftn grew. In 1892, there were 87 landsmanshaftn comprising communities of Eastern European Jews in New York City6. With the largest wave of Jewish immigrants coming in the early 20th century, so too came more landsmanshaftn; by 1910, there were over 2,000 recognized landsmanshaftn in New York City7. As New York City developed into a hub for American Jewry, it also became a hub for landsmanshaftn.

Apart from the tangible benefits of mutual aid and burial, these landsmanshaftn also provided a buffer space for Jewish immigrants. The U.S. was a different environment than those from which many Jewish immigrants came, and the forces of assimilation could often be as daunting as they were enticing.

Meeting in a landsmanshaft allowed Jewish immigrants to retain some Old Country tradition, culture, and way of being, though physically in New York City. It allowed many to feel connected to both their new home and their old home, creating a space for shared memory to be actualized while reconciling with a foreign land8. In addition to social services, landsmanshaftn were vehicles for a special type of community that proved crucial in Jewish New York.

The evolution and decline of landsmanshaftn

These special communities did not remain static. Jewish life in New York changed rapidly over the course of the 20th century, and so did the role of landsmanshaftn. Jewish immigrants had native-born American children, who only knew the Old Country from whispers and stories.

defunct Chevra Beth David Anshe Stebechve.

With the decline of landsmanshaftn and

older generations passing away, many

of their plots have seen disarray.

In addition to being further removed from the experience of the Old Country, many in this generation of Jewish New Yorkers formed community differently. They spoke English natively, they went to American schools, and many primarily thought of themselves as American. Old Country origins mattered less for them.

By the 1950s, landsmanshaftn began to decline9 as this next generation was less involved, less interested, and less reliant. Many native-born children did remain involved, but as time went on, the ranks of landsmanshaftn suffered heavy losses at the deaths of the immigrant generation10. By the next generation, many landsmanshaftn were defunct.

The declining involvement in landsmanshaftn has presented a problem for Jewish cemeteries. If a landsmanshaft owns a plot for its members but becomes defunct, how can they facilitate burial into the future? While some landsmanshaftn deeded out graves to their members and members’ children, many did not. This disarray has created issues for the spouses and children of people buried with a landsmanshaft, who sometimes cannot be buried next to their relatives11. Other children of landsmanshaft members have no interest in being buried with the landsmanshaft plots, and some don’t even know they have plots.

Today, few landsmanshaftn remain in existence. For those that survive, the expansion of the landsmanshaft’s scope and community served allows for continued operations and relevance in American Jewish life. However, despite the organizational decline today, many physical remnants of landsmanshaftn’s once-thriving past still remain. These physical remnants—like cemetery plots, incorporation paperwork, and meeting records—can help you discover more about your Jewish ancestors, who lived in a time when landsmanshaftn thrived.

Locating and researching landsmanshaftn

The remnants of landsmanshaftn can help reveal more about your ancestors’ involvement with a landsmanshaft and often includes other details of a person’s life.

A good place to start investigating an ancestor's membership in a landsmanshaft is the cemetery. Members of landsmanshaftn were often buried with other members of the landsmanshaft in communal plots. The people buried together often had ties in the Old Country and in New York City, and many times one can find an ancestor’s relatives in a landsmanshaft plot.

fun Nyu York” (1938) detailing New York

landsmanshaftn, their purpose,

leadership, and membership growth

over time.

Figuring out your ancestor’s cemetery of burial is a helpful first step. Death certificates often list the place of burial, and many Jewish cemeteries allow you to search the people buried there with a locator tool online. These locator tools often list the deceased’s landsmanshaft if buried with one, though the cemetery office can also likely inform you of this information.

Once you know the name of a landsmanshaft, it’s time to research further. Landsmanshaftn were often organized around a geographic location in the Old Country, so this may be helpful to determine where your ancestors originated before the United States. A plot often contains relatives and close friends as well, so knowing who else is buried there can help build your family tree. An in-person visit is best; be sure to take lots of photos, which may prove useful later. Also check out the gates or pillars marking a landsmanshaft’s plot, as they often contain names of members. A landsmanshaft, depending on the size, could even have plots in more than one cemetery, so it’s important to consider all of a landsmanshaft’s plots.

There are also archives on landsmanshaftn that could provide more information about your ancestors. Knowing the name of the landsmanshaft they were involved with, you can search for incorporation papers or membership information. Access to many of these records can be found on the Center for Jewish History, YIVO, and Jewish Genealogical Society websites. Also, be sure to check JewishGen for more information about the landsmanshaft’s town of origin and associated records from the Old Country.

While landsmanshaftn do not exist in the number or strength that they once did, these communities informed our ancestors’ experiences, and—through genealogical investigation—can teach us more about their lives in New York City. The case of landsmanshaftn shows how American Jewish community has evolved since the arrival of our ancestors, and how it continues to do so as we navigate our experience in the diaspora.

Citations

1. Morris, Tanisia. “Tracing the History of Jewish Immigrants and Their Impact on New York City.” Fordham Newsroom, 23 Feb. 2018, news.fordham.edu/inside-fordham/faculty-reads/tracing-history-jewish-immigrants-impact-new-york-city/.

2. Sachar, Howard M., “Landsmanshaftn.” A History of the Jews in America, Vintage Books, 1992, www.myjewishlearning.com/article/landsmanshaftn/.

3. Kaganoff, Nathan M. “The Jewish Landsmanshaftn in New York City in the Period Preceding World War I.” American Jewish History, vol. 76, no. 1, Sept. 1986, pp. 56–66. 61

4. Sachar, Howard M., “Landsmanshaftn.” A History of the Jews in America, Vintage Books, 1992, www.myjewishlearning.com/article/landsmanshaftn/.

5. Kaganoff, Nathan M. “The Jewish Landsmanshaftn in New York City in the Period Preceding World War I.” American Jewish History, vol. 76, no. 1, Sept. 1986, pp. 56–66. 59

6. Sachar, Howard M., “Landsmanshaftn.” A History of the Jews in America, Vintage Books, 1992, www.myjewishlearning.com/article/landsmanshaftn/.

7. Ibid.

8. Soyer, Daniel. “Between Two Worlds: The Jewish Landsmanshaftn and Questions of Immigrant Identity.” American Jewish History, vol. 76, no. 1, Sept. 1986, pp. 5–24.

9. Ackman & Ziff Family Genealogy Institute. “Landsmanshaftn.” Center for Jewish History, Center for Jewish History, Sept. 2008, www.cjh.org/pdfs/Landsmanshaftn07.pdf.

10. Vitello, Paul. “With Demise of Jewish Burial Societies, Resting Places Are in Turmoil.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 2 Aug. 2009, www.nytimes.com/2009/08/03/nyregion/03bury.html.

11. Ibid.